Joseph Alter: Exploring Health, Athleticism, and Nationalism in India

The pehalwan (wrestler) wakes at 4 a.m., like the others in his akhara (gymnasium). This is his guru’s time. He massages his coach’s feet, prepares his breakfast, washes his clothing. (Serving his guru is part of his training, just as much as the physical practice of wrestling.) Next comes the grueling work of digging the wrestling pit with a heavy spade. Once the earth has been turned and softened, the pit must be prepared by mixing oil, buttermilk, turmeric, and rosewater into the soil. This enhances the natural essence of the earth and promotes fitness and health.

The pehalwan (wrestler) wakes at 4 a.m., like the others in his akhara (gymnasium). This is his guru’s time. He massages his coach’s feet, prepares his breakfast, washes his clothing. (Serving his guru is part of his training, just as much as the physical practice of wrestling.) Next comes the grueling work of digging the wrestling pit with a heavy spade. Once the earth has been turned and softened, the pit must be prepared by mixing oil, buttermilk, turmeric, and rosewater into the soil. This enhances the natural essence of the earth and promotes fitness and health.

By this time, it is 5 a.m. and still dark. The other pehalwans wait for their turn in the pit. They wrestle for two hours, becoming caked with the moist earth as the sun rises. Tradition dictates that the mud dries on the skin, before it is scraped off, returning the sweat-saturated earth to the soil from which power is drawn. After the work of wrestling, the pehalwans are ready to eat. They prepare a mixture of crushed almonds, milk, and ghee (clarified butter) as a tonic supplement—they will drink as much as two liters of this Indian version of a protein shake.

Though this day-in-the-life-of routine could have taken place several centuries ago, these rituals are still observed today. For modern-day Indian wrestlers in Banaras and other parts of North India, this strict regime is part of a masculine tradition that focuses on strength, self-discipline and—oftentimes—abstinence.

***

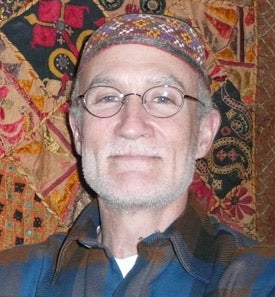

Joseph Alter became fascinated with the elaborate way of life associated with Indian wrestling when he was a teenager, living in the scenic resort town of Mussoorie high in the mountains of Northern India.

“I started wrestling when I was about 16 or 17,” Alter recalls. “I was never a good wrestler, but the exercise regimen of akhara life took hold of my imagination—and my body—and became an intellectual obsession as well.”

Alter, professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh, was born and raised in Mussoorie. He is part of a line of Presbyterian missionaries, stretching back to both his grandparents (who moved to India in 1917) and both of his parents. He has drawn upon the rich material of his upbringing in India to inform his work today. His latest book is Moral Materialism: Sex and Masculinity in Modern India, Penguin India, 2011.

“Most people think about sex as an act that is linked to desire, pleasure, and/or procreation,” says Alter. “For some men in India, especially within the context of athletics and yoga, sex is focused on the question of how you develop your own body, rather than how your body comes into contact with the body of another person.”

His book cover depicts a muscular Indian wrestler struggling with a lion. It is borrowed from a contemporary Indian pamphlet for aphrodisiac recipes. But, the Indian view of aphrodisiacs strays quite a bit from what our Western sensibilities would assume.

“Aphrodisiacs do not just produce sexual prowess; they are designed to promote physical strength and good health, as well as other things,” says Alter. “The image captures the main argument I make in the book—the physiology of masculine sexuality is about physical strength and material power, not about desire and erotic excess.”

***

Alter moved to the United States in 1977 for college, opting for Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. But, it was not an easy transition.

“I was at loose ends and rather disoriented,” says Alter. “Small towns on the east coast are rather parochial in comparison to the cosmopolitan cultural diversity of small towns in the Himalayas.”

But, that changed when Alter signed up for an introductory anthropology course. One day, while browsing the campus library, looking for an ethnography to use for his book review assignment in anthropology, Alter came upon a classic written by Gerald Berreman. It was based on ethnographic research done in a village only 15 miles from his home in Mussoorie.

“I suddenly realized that with training in anthropology, I could kill at least two birds with one stone… Pursue a career in academia, but do so by navigating my way back home to do research in India.”

Alter pursued his work avidly, earning his bachelor’s degree in social/cultural anthropology at Wesleyan, and then studying under Berreman, who became his mentor and dissertation advisor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he completed his master’s and doctoral degrees.

***

This summer finds Joseph Alter immersed in his latest research—quite literally.

He recently won a four-year, $120,500 National Science Foundation grant to study “Ecological Health and the Embodiment of Nature: Environmentalism, Social Class and Nature Cure in Modern India.”

Or, as he puts it: “I plan on spending the next three years immersing myself in mud baths, steam baths, and various forms of water cure in order to try and understand why these historically European therapies are now more popular in India than anywhere else in the world.”

Alter has been traveling to India to conduct research for just over 30 years and returns on various projects almost every year. Much of his research has taken place in the Himalayas, where his first project was on cultural change and the economics of dairy farming; then, in the city of Banaras, where he spent a year in a wrestling gymnasium; and then in Delhi, where he spent the better part of a year practicing asana and pranayama (yoga postures and breathing) and studying a nationalist yoga organization.

Alter has published extensively on topics of health and the body, particularly as they relate to cultures in India and South Asia. His books include: Yoga in Modern India: The Body Between Philosophy and Science, Princeton University Press, 2004; Gandhi’s Body: Sex, Diet and the Politics of Nationalism, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000; Knowing Dil Das: Stories of a Himalayan Hunter, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000; and The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India, University of California Press, 1992.

***

Alter joined the Pitt faculty as a visiting professor in 1994 and steadily moved up the ranks to full professor, and, most recently, chair in 2006. He is enthusiastic about his department’s future—as well as that of the entire University.

“I’ve been teaching at Pitt since the mid ‘90s, and the University has changed significantly. Each year it seems as though students get better and better. They are more self-motivated, more engaged in the project of public education, and more determined to succeed. As a result, they demand more of us as faculty; and that is a very good thing.”

Alter likes the fact that his students keep him and his colleagues on their toes. In fact—despite Alter’s personal commitment to research—he is convinced that higher education’s true value is reflected in teaching, first and foremost.

“Research produces important, tangible results that can be tabulated and used in various practical ways; but teaching…,” says Alter. “Teaching opens up space for true intellectual creativity within our students and their translation of old ideas into new concepts.”

To learn more about Joseph Alter and his work, visit www.anthropology.pitt.edu/faculty/alter.html.